Cabinetmakers in Empire New York City

Edward Holmes and Simeon Haines

Through the eyes of a cabinetmaker in the 1820s, New York City must have surely resembled a paradise of opportunity. Cheap immigrant labor, myriad patrons willing and able to purchase furnishings in the newest styles, and the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825, which expanded commerce westward, created numerous opportunities for financial gain. Between 1820 and 1850 the population of the city swelled by more than 60 percent to more than two hundred thousand inhabitants, (1) and the demand to furnish their houses with objects of status rose dramatically. Among the many furniture makers who responded to this demand was the partnership of Edward Holmes and Simeon Haines, which was established in 1825.

Edward Holmes was born between 1780 and 1790 and first appeared in the 1821-1822 New York City directory as a cabinetmaker located on Broad Street at the corner of Stone Street in Manhattan. The value of his property at this time, which included the contents of the shop, was assessed at three thousand dollars, and it grew to eighty-five hundred dollars by the time Holmes and Haines was initiated. (2) Simeon Haines was born in Burlington, New Jersey, on August 30, 1800. (3) He first appears in the city directories when the firm of Holmes and Haines began operations at 20 Beaver Street. Haines's previous training in furniture production has not been established, but he presumably had some skills since he became a partner in a furniture-making business. His wife, Elsey Ann Holmes (1806-1883), may have been one of Edward Holmes's relatives. (4)

When the firm of Holmes and Haines began operations, competition between New York cabinetmakers was fierce. Established and well-respected craftsmen such as Michael Allison, Deming and Bulkley, Joseph Meeks and Sons, and Duncan Phyfe were all working at this time. In fact, Joseph Meeks (1771-1868) owned the properties at 43, 45, and 50 Broad Street in very close proximity to Holmes's shop at 48 Broad Street. This competition may very well explain why Holmes and Haines possibly supplemented their income by holding auctions at their 151 Broadway location in 1828, where they offered carpets, glassware, curtains, books, jewelry, pianofortes, paintings, rare engravings, and even coats, in addition to new and secondhand furniture. (5)

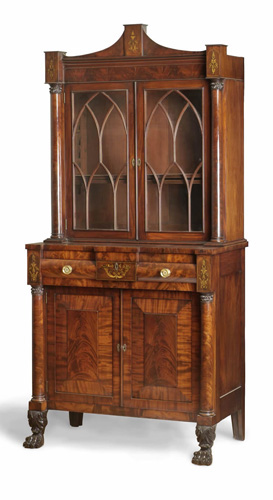

The furniture produced by Holmes and Haines was typical of the Empire style in New York City, with mahogany usually serving as the primary wood, often elaborate stenciled decorations, acanthus-based carvings, and gilt-brass mounts. Although only seven extant pieces with a Holmes and Haines label or a stenciled mark are currently known, they offer a good representation of the quality of furniture sold by the shop, which, when judged purely on an aesthetic basis, appears to have been  intended for New Yorkers who had more rather than less disposable income. The group consists of two dressing bureaus, two pier tables, one card table, one worktable, and one sideboard.

intended for New Yorkers who had more rather than less disposable income. The group consists of two dressing bureaus, two pier tables, one card table, one worktable, and one sideboard.

The dressing bureau is distinctively New York, with its flaring scrolled mirror supports, stenciled facade, and heavy paw feet. (6) It bears a paper label engraved "H. & H." at the top and the number 154 handwritten on the bottom, probably an inventory number of some type. The other known Holmes and Haines dressing bureau bears a stenciled mark that includes two addresses--48 Broad and 20 Beaver Streets--dating it to 1825 to 1826, the only years the firm is listed at both those addresses. The main visual differences between the two labeled examples is that the one has two vertically stacked drawers under each of the carved mirror brackets. Several other examples of this form have come onto the market over the years attributed to Holmes and Haines, but dressing bureaus were also produced in other New York shops, so attributions must be considered very carefully. (7) The labeled Holmes and Haines pier table epitomizes the refined style New Yorkers fancied at the time, with the bold Doric marble columns of the Greek revival movement, cornucopia stenciling, and carved lion's paw feet below gilded foliated wings. (8) It too bears the engraved H. & H. label, inscribed with the handwritten number 58. The other pier table, which is thought to have been made for the Pierpont family of Brooklyn, (9) is a more modest variation of the form. Its H. & H. label is inscribed with the number 146 in pencil. The only known card table and sideboard from the shop are presently known only through photographs in auction catalogues. Both bear the H. & H. label, the one affixed to the sideboard inscribed with the number 144. (10) The only known worktable from the shop bears the same stenciled mark as the dressing bureau, but it has been printed on a paper label. (11)

In the summer of 1828, Holmes and Haines held a sale at a wareroom at 151 Broadway, the only year they were located there, in which

Every article intended to be offered has been got up by the proprietors in the most superior manner, and as such is warranted with the utmost confidence, and upon examination will be found, in every respect, the most choice and fashionable selection ever offered to the citizens of this city.... In the sale will be found the most approved French & English taste, viz--Dining, tea and centre tables, on pillar and claw feet; pier, card and dressing d[itt]o of entire new style, with 4, 2 and single pillars, some in the harp form; elastic seat sofas and couches, with the proprietors new invented arch back, which is not surpassed by any in the city.12)

The results of the sale are not known, but by late September 1828, an A. A. Waterhouse (possibly Abraham A. Waterhouse who was listed in the Albany directories as owning a looking-glass store there until 1825) was holding furniture sales at Holmes and Haines's 151 Broadway location. (13) In early December 1828, Waterhouse, by order of the assignees Holmes and Haines, advertised an upcoming sale of the firm's entire stock of cabinet furniture. (14) In the 1829-1830 directory Waterhouse is listed as a merchant at the 151 Broadway address, so he presumably purchased the property from Holmes and Haines. The partnership of Holmes and Haines is listed in that directory for the last time, at Twentieth Street near Sixth Avenue.

The 1830 federal census lists Holmes's household with fifteen residents (eleven males and four females), but it is not possible to determine if they were all related. (15) He is listed alone as a cabinetmaker at 229 Twentieth Street in the directory for 1830-1831, but then he disappears from directories and other records until 1834, when he again claims the profession of cabinetmaker at 73 Broad Street. He is so listed in the 1836-1837 and 1837-1838 directories at 58 Broad Street; in the 1840-1841 edition at 122 Broadway; in 1841-1842 at 102 Broadway; and finally in the 1844-1845 edition at 408 Washington Street. Real estate records show that his inventory was valued at fourteen thousand dollars in 1835 and 1836 and at twenty-two thousand dollars in 1841. (16)

Haines is listed as an individual cabinet-maker at 56 Broad Street in the directories from 1830 to 1833, moving the next year to 58 Broad, where he was listed until 1840. He retired from cabinetmaking about 1845 and then made quite a sum of money in stock investments (valued at almost one hundred thousand dollars in 1855) before opening up a flour business called Simeon Haines and Son, with his son Provost S., in 1855 at 117 Warren Street. (17) Haines died on March 30, 1879, and is buried alongside his wife, their daughter Lavinia Beatrice Haines Stearns (1830-1877), and son-in-law Bernard Stearns (1815-1880) in the Poughkeepsie Rural Cemetery in Poughkeepsie, New York.

The card table in Plate VIII and a pier table in the collection of the Museum of Arts and Sciences in Daytona Beach, Florida, (18) are of great interest because they both bear the label of Holmes alone (the only known pieces by him alone) and the date 1830. However, the address on the label is 56 Broad Street, which records show as Haines's property at that date. (19) In addition, both men are listed as cabinetmakers at 58 Broad Street in the 1836-1837 and 1837-1838 directories. Thus, they seem to have stayed on good terms even after dissolving their partnership and possibly individually produced wares out of the same location, although to date no objects attributed to or labeled by Haines alone have come to my attention. Of course, this information also proves to be problematic for dating surviving pieces that bear the H. & H. label; for the two men could also have jointly made furniture after the breakup of their partnership, or simply continued to use old labels.

With their combined cabinetmaking careers totaling more than forty years, Holmes and Haines surely produced many more objects than have so far been identified. We can only hope that more examples become available for study; for this will strengthen our understanding of these craftsmen and the society they catered to.

(1) Ira Rosenwaike, Population History of New York City (Syracuse University Press, Syracuse, New York, 1972), p. 36.

(2) Record of Real Estate Assessment, 1825, Manhattan, Ward 1 (microfilm in the department of records and information services, Municipal Archives, New York City). The 1825 dollar amount includes two locations (48 Broad and 20 Beaver Streets). Advertisement

(3) Simeon Haines's place and date of birth are found at www.familysearch.org.

(4) Ibid., and Haines/Stearns family monument in the Poughkeepsie Rural Cemetery, Poughkeepsie, New York.

(5) See, for example, their advertisement in the New-York Gazette and General Advertiser, June 23, 1828.

(6) For a Boston interpretation of this form, see Elizabeth Feld and Stuart P. Feld, Of The Newest Fashion: Masterpieces of American Neo-Classical Decorative Arts (Hirschl and Adler Galleries, New York, 2001), pp. 54-55, No. 22.

(7) For an example produced by Alexander P. W. Kinnan and States M. Mead (w. together 1823-1830) of New York City, see Wendy A. Cooper, Classical Taste in America 1800-1840 (Abbeville Press, New York, and Baltimore Museum of Art, 1993), p. 220, Fig. 177.

(8) For a very similar example, see Charles L. Venable, American Furniture in the Bybee Collection (University of Texas Press, Austin, in association with the Dallas Museum of Art, 1989), p. 122, No. 55.

(9) American decorative arts department archives, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City.

(10) For a similar example of the form produced by Duncan Phyfe (1768-1854), see Jerry E. Patterson, The City of New York: A History Illustrated from the Collections of the Museum of the City of New York (Harry N. Abrams, New York, 1978), p. 106, No. 127.

(11) For a very similar example, see Fine Americana, Sotheby's, New York, January 28, 30, 31, 1994, Lot 1073.

(12) New-York Gazette and General Advertiser, June 28, 1828.

(13) Ibid., September 27, 1828.

(15) The United States Census for 1820, New York lists an Edward Holmes in Rhinebeck, in Dutchess County, but it is unclear if this is the same man that this article is focused upon.

(16) Record of Real Estate Assessment, 1835, 1836, and 1841, Manhattan, Ward 1 (microfilm in the department of records and information services, Municipal Archives, New York City).

(17) Sub. of Provost S. Haines, New York City, vol. 10, p. 553 (R. G. Dun and Company Collection, Baker Library, Harvard Business School, Boston).

(18) Illustrated in Gary R. Libby, A Treasury of American Art: Selections from the Collection of the Museum of Arts and Sciences (Museum of Arts and Sciences, Daytona Beach, Florida, 2002), pp. 110-111.

(19) Record of Real Estate Assessment, 1830, Manhattan, Ward 1 (microfilm in the department of records and information services, Municipal Archives).

ERIK RINI is an antiques dealer, adviser, and scholar in the field of early American decorative arts in New York's Hudson Valley.